The deeper I work with agentic systems, the more I realize that designing them feels a lot like building and leading engineering teams. The same principles that help humans work together — clarity, accountability, delegation, and orchestration — also govern whether autonomous agents deliver business value or generate chaos.

This isn’t just a metaphor. It’s a design pattern.

Here’s how to apply those leadership lessons directly to the architecture of multi-agent systems.

Directives Are the New Requirements

In a human team, unclear goals lead to wasted sprints and duplicated work. In an agentic system, the result is even worse: runaway token usage, inconsistent outputs, and “AI slop.”

Every agent you design needs three fundamental inputs — think of them as the “job description” in software form:

- Mission: The specific goal the agent is meant to accomplish.

- Constraints: The boundaries and guardrails (e.g., tone, compliance, cost, latency) that define “good.”

- Deliverables: The expected output shape — JSON schema, Markdown summary, structured SQL, etc.

Tip: Treat your system prompt like a spec document. The clearer the contract, the more predictable the performance.

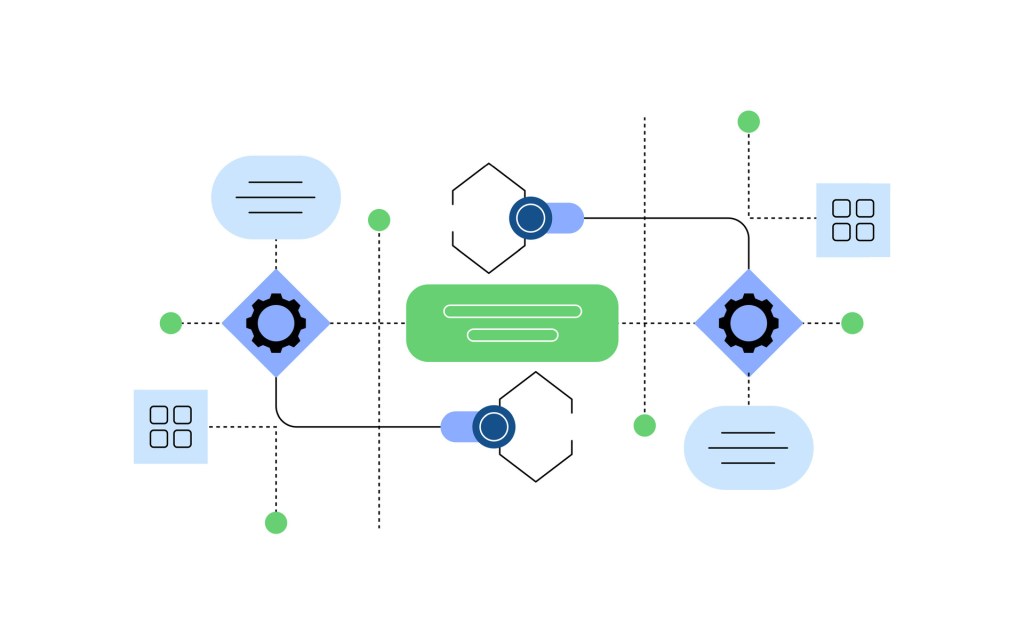

Roles, Crews, and Modular Architectures

A common anti-pattern in early agent development is the “Swiss Army Knife” agent — one LLM instance trying to do everything. It’s the equivalent of hiring a single engineer to handle frontend, backend, DevOps, data science, and QA.

Instead, compose agents into modular “crews” — each with a single responsibility and well-defined interfaces.

Example: Documentation Pipeline

Researcher

- Mission: Gather technical specs and user stories

- Input: Feature ID

- Output: Structured notes

Draft Writer

- Mission: Convert notes into a structured documentation draft

- Input: Researcher output

- Output: Markdown draft

Editor

- Mission: Check draft for accuracy, tone, and readability

- Input: Draft Writer output

- Output: Polished draft

Publisher

- Mission: Push final draft to docs site or repository

- Input: Editor output

- Output: Deployment confirmation (JSON)

Each agent runs independently and can be retrained or replaced without disrupting the others. Together, they behave like a small writing team — coordinated by an orchestration layer.

Orchestration Patterns: From Linear to Dynamic

The orchestration layer is where “leadership” really lives. It decides who does what, in what order, and how results flow.

Here are three common patterns to consider:

Linear Pipeline

Each agent runs sequentially. Ideal for workflows with clear dependencies (e.g., ETL → Analysis → Report Generation).

graph LR

A[Input] --> B[Agent 1: Parse] --> C[Agent 2: Enrich] --> D[Agent 3: Format] --> E[Output]Parallel Specialization

Multiple agents work independently on sub-tasks and their results are merged. Great for decomposing complex prompts into smaller expert tasks.

graph LR

A[Input] --> B[Agent: Research]

A --> C[Agent: Analysis]

A --> D[Agent: Draft]

B --> E[Merger]

C --> E

D --> E

E --> F[Final Output]Dynamic Planning (Planner-Executor)

A “planner” agent breaks a problem into subtasks, then routes them to specialized executors. This mirrors how a tech lead delegates work in a sprint.

graph TD

A[Planner] --> B[Executor 1]

A --> C[Executor 2]

A --> D[Executor 3]

B --> E[Aggregator]

C --> E

D --> E

E --> F[Final Output]💡 Best practice: Start with a simple linear orchestration and evolve into dynamic planning once you trust the system’s reasoning reliability.

Accountability: Instrumentation and Feedback Loops

Leadership is about more than assigning tasks — it’s also about measuring results. The same applies to agent networks.

Here’s how to embed accountability into your orchestration layer:

- Structured outputs: Enforce JSON schemas or typed responses to validate agent output before the next step.

- Validator agents: Add “judge” agents to score quality, accuracy, and compliance.

- Performance metrics: Track token usage, latency, error rates, and hallucination incidents.

- Self-reflection loops: Allow agents to critique or refine their own responses before returning results.

Example validation step:

{

"task": "Summarize meeting transcript",

"validation_rules": [

"Summary < 200 words",

"Must include key decisions",

"No speculative language"

],

"score": 0.92

}Emergence: Designing for Collective Intelligence

Just as high-performing teams exhibit emergent behaviors (innovation, resilience, creativity), so do well-orchestrated agent systems. But emergence doesn’t happen by accident — it’s designed into the system through:

- Well-defined interfaces (clear API contracts between agents)

- Feedback visibility (agents know the downstream impact of their work)

- Shared memory (access to shared context like knowledge graphs or vector stores)

- Adaptive orchestration (ability to reprioritize or redistribute work dynamically)

When those conditions exist, the network becomes more than the sum of its parts. Agents begin to collaborate rather than simply coordinate.

Leadership as Infrastructure

The ultimate insight here is that orchestration is leadership, expressed as infrastructure.

- System prompts are your strategic plans.

- Agent interfaces are your org charts.

- Orchestration logic is your management cadence.

- Metrics and validators are your performance reviews.

When you embed these patterns into your system design, agent networks stop behaving like a collection of isolated models — and start functioning like a cohesive engineering team.

Final Thought

Agentic AI encodes already strong leadership — it’s not a replacement. And the teams who learn to translate leadership principles into technical architecture will be the ones who unlock its true potential.

The future of engineering isn’t about controlling every detail. It’s about designing the systems that can self-direct, self-improve, and scale beyond what we could ever manage manually.